By: Megan Eckstein

April 9, 2019 9:49 AM

Harry S. Truman Carrier Strike Group participates in a strait exercise in the Atlantic Ocean on April 7, 2019. US Navy Photo

THE PENTAGON – The Navy’s Fiscal Year 2020 budget request includes tectonic shifts in how the Navy does business – swapping a Nimitz-class aircraft carrier for unmanned surface vehicles and other technologies – and it comes even as the service is reevaluating what sized fleet and what mix of ships the Navy needs to meet future challenges.

Though a force structure assessment tends to guide acquisition decisions in the budget process, the Navy has made clear that the most recent FSA is dated and that service leaders are going through the process of compiling a new one, due out at the end of this calendar year.

So, with the current FSA being null and void, what guided the Navy’s big budget decisions this year?

“The National Defense Strategy defines the vision of the military,” Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Warfare Systems (OPNAV N9) Vice Adm. Bill Merz told USNI News.

“The Navy is going to be a part of a much more lethal, distributed, agile joint force.”

“That vision has not changed, and that’s what we’re after. That’s what drove the 355-ship navy under the last FSA, and we’ll see what this one – we expect the requirement probably to go up this time just because of the distributed maritime operations concept that the fleets are employing now that drives a lot of enabling requirements like logistics,” the admiral continued.

Merz noted that FSAs typically only last a few budget cycles and that it’s normal to redo them periodically. But many things have changed since the last FSA was released in December 2016: the Trump Administration took office, former Defense Secretary James Mattis penned a new National Defense Strategy, the Navy adopted a distributed maritime operations concept that changes how the fleet would operate and sustain itself, new leadership in all the combatant commands have taken over, the frigate program has matured and appears much more capable than previously thought, the submarine industrial base is struggling to keep up even as its workload is increasing, and much more.

Merz acknowledged that the upcoming FSA will likely be very different than the one on the books today. But he also said that the Navy’s budget submission was well informed despite the lack of an FSA to guide it.

“We are constantly doing wargames and analysis. It’s the same analysis, threat vectors, intelligence reports that get fed into the FSA. So it’s not the FSA driving those; the FSA’s just a beneficiary of it, like so many other things we look at,” he said.

“So we don’t need the FSA to tell us we need unmanned systems or directed energy, rail guns and that sort of stuff. Those are done by threat analysis for specific threats and capability gaps that those threats generate that we know we have to fill. How much of it we need based on a campaign plan or an [operational] plan? The FSA will have an opinion on how many of those things do you need, where do you need them, what kind of platforms need to be carrying them, that sort of stuff. But the actual capabilities, we have other methods through our research labs and everything else that determine that.”

Another driving factor in the Navy’s FY 2020 budget request is balance. Merz brought up balance many times during the interview with USNI News, noting that the fleet could not outsize the Navy’s ability to sustain it, man it and modernize it.

“Understanding exactly what we need for readiness drives how much we can invest in the future. So the readiness is the here and now, and the investments are the capabilities we’re trying to bring into these accounts,” he said.

“We have funded virtually every maintenance account, whether air or surface ship, to what we call the max executable rate. … Matter of fact, we have an unfunded priority list that adds even more because industry has told us, hey, we think we can execute a little more.”

Still, the Navy is struggling to understand what those costs will be as the Navy grows larger.

“We had been shrinking the Navy for 40 straight years – that includes aircraft and ships and everything else – so there’s a new addendum in the shipbuilding plan about sustainment, what the cost is going to be to sustain that 355-ship navy. We don’t really even have the complex modeling to figure that out, so that’s one of the things we’re working on is developing the models,” Merz said.

“We have one of the largest budgets ever, and it’s sustaining about a 300-ship navy, not a 355-ship navy. We have to get a lot more efficient, we’re going to need a lot more resources, or god forbid we have to get smaller again – and that just creates a lot of risk in what we’re trying to do. Good news is, I think everybody is rallying around this. They understand the chore, it’s ahead of the panic, it’s about 10 to 20 years out – but it does give you a sense for what that challenge is going to be and we’re going to have to start working on it.”

The Navy took a turn under former Navy Secretary Ray Mabus to grow in size, ending that decades-long shrinkage, but Merz said sequestration and other factors led the Navy to make the decision to grow in an unbalanced way.

“We came through a period, and Secretary Mabus did what he could, but that was an era of untenable decisions: you’re either going to buy a ship or you’re going to pay for readiness. Some years we did one, some years we did the other. And in the end we found ourselves pretty far out of balance on readiness. And some of the challenges have manifested in horrible ways, and we’re not going to go back to being an unbalanced navy – so whatever sized navy we are, it’s going to be a balanced navy. The proper investments in readiness versus the proper investments in the advanced capability.”

Merz said the renewed focus on readiness to create a balanced force began in 2016 and is already showing results. Aviation readiness rates, which at times dropped below 50 percent, have “taken dramatic turns lately in a positive direction” thanks to funding spares, logistics, engineering and depot maintenance accounts to the maximum executable levels for the last few budget cycles. Rear Adm. Scott Conn told lawmakers last week that those rates now bounce between about 63 percent and 75 percent for Super Hornets – just short of the 80-percent mission capable rate the services are aiming for in their fighter fleets.

“We’re on a very aggressive recovery ramp. We’re very pleased that the recovery effort that essentially started in FY ’16 and ’17. When we turned that spigot wide open, we all kind of got into a pile-on with industry trying to make this maintenance a lot more efficient, and it’s starting to pay off now. I think we’re pretty satisfied that we turned it; we’re not satisfied until we see that we can sustain this ramp. And then once we get to the target of 80 percent, which is the [tactical aircraft] number but internally we’re applying that to [all aircraft] … is there enough enduring reform there and efficiencies to make sure we stay there? And that’s what we’re after. Right now the vectors are positive … and now the trick is to not take your foot off that pedal.”

Balance also means making the fleet more lethal and more netted, to support the distributed maritime operations concept, Merz said.

“Directed energy, hypersonics – those are the types of capabilities we’re most interested in, and you see a fairly significant push and support money to get those things fielded. Railgun is still a little bit nascent for us, that’ll just compete against a lot of other capabilities in that same family. We’re not wedded to railgun; we’re very interested in the technology, but like a lot of technologies, we’re committed to it until we have to compete it against something else and we’ll see how it does,” Merz said on the lethality piece.

On networks, he declined to dive into too many details, but he said the Navy Tactical Grid and the Joint Tactical Grid will be important to the way the Navy hopes to do business in the future.

“We know these netted effects are really where we need to get to to maximize the lethality out of any fighting force we have. We’re a large, powerful navy; but we’re a large, powerful navy distributed all over the planet. So in any particular part of the world, we may not be so large, and the way we get after that is just making sure we’re connected and netted and we can coordinate the effects we need,” he said.

Merz said the Navy had lost sight of this balance before but vowed not to do it in the future. A top priority, he said, is “remaining balanced in the Navy – don’t over-commit to readiness, don’t over-commit to investment. It’s kind of like the rising tide floats all ships kind of thing – we have a history of leaving a few of those ships behind, and I don’t think you’re going to see us do that again.”

Navy’s 355 Ship Fleet Infogram

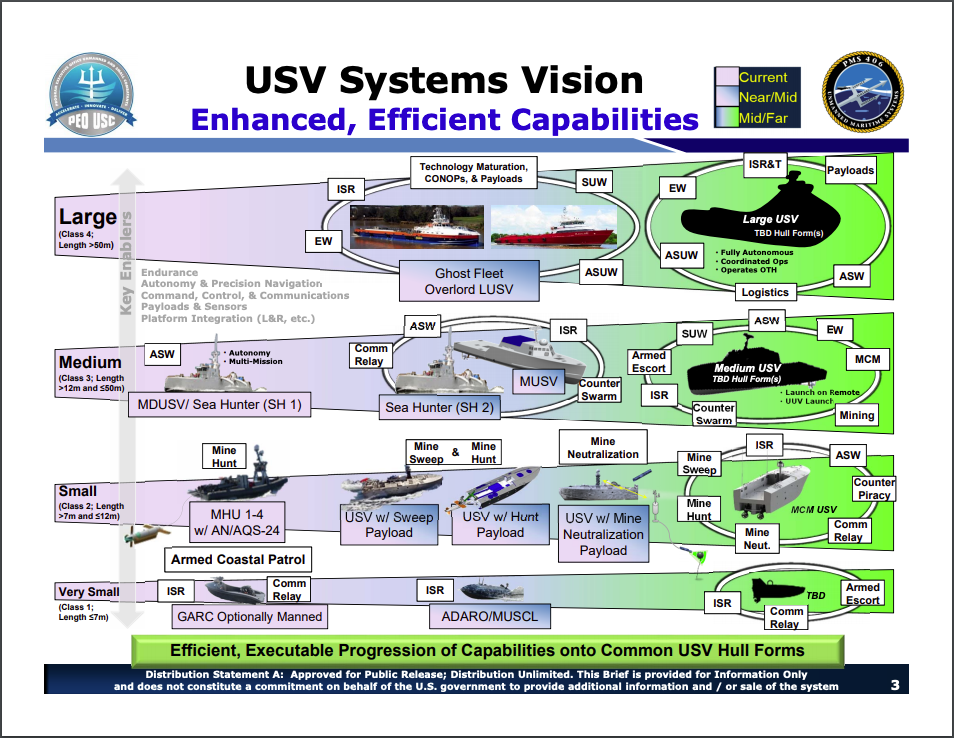

US Navy’s unmanned surface concept. NAVSEA Image

Artist’s concept of a HELIOS laser system aboard a U.S. destroyer. Lockheed Martin Image